AAP leader and Punjab Chief Minister Bhagwant Mann chaired a meeting of his cabinet that decided to return to the old pension scheme for the state’s government employees while the INC is promising it in the campaign for the Himachal Pradesh election. The AAP has promised it also to the pensioners in Gujarat in its campaign. Two Congress-ruled states, Rajasthan and Chhattisgarh, have already decided to implement the old pension scheme. Jharkhand has decided to return to the old pension scheme too.

This is a step the Reserve Bank of India has seriously advised against and the union government of Narendra Modi and the BJP do not want to withdraw the new pension scheme.

But the economically sound decision of the BJP is fraught with the risk of being unpopular at the hustings. The salaried class from government services is known to be a voting bloc that, unlike the rest of the middle class, cares for its own interest at the expense of national interest. Pension beneficiaries in different states have been vociferously demanding a return to the old scheme quite expectedly.

But why is the old pension scheme bad for the economy?

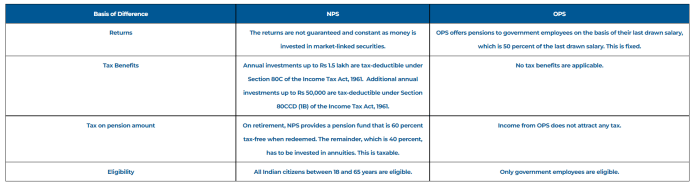

Differences between old and new pension schemes

The old pension scheme entailed payment of 50% of the employee’s salary every month to him or her post-retirement. This financial burden is borne entirely by the state.

The new pension scheme, in contrast, is contributory. The concept is like the sharing model in the employee provident fund. The employee contributes 10% towards the pension whereas the government pays 14%. This helps reduce the burden on the exchequer.

Who is eligible for the old pension scheme and who will get the new one?

The cut-off date is 1 April 2005. Indian government employees who retired before this date continue to get pensions under the old scheme whereas those who retired after the said year are slotted under the new scheme.

Why did the union government switch to the new pension scheme?

The switch happened during the Atal Bihari Vajpayee government’s final days in 2004, but it enjoyed the support of not only the BJP but also the INC when the Manmohan Singh government followed.

It was a wise way of managing politics as much as economics. For, the size of the population that turned 60 years old in 2005 will only reduce with the passage of time, thus gradually reducing the pressure on the exchequer.

Since this is a phasing-out mechanism, the beneficiaries will not get a sudden shock, which could have political repercussions.

Why are AAP and INC wrong?

If every pensioner goes back to the old pension scheme, which these parties are promising to the people, the population of pensioners will keep increasing — thanks also to the ever-improving life expectancy of Indians — adding more and more burden to the treasury.

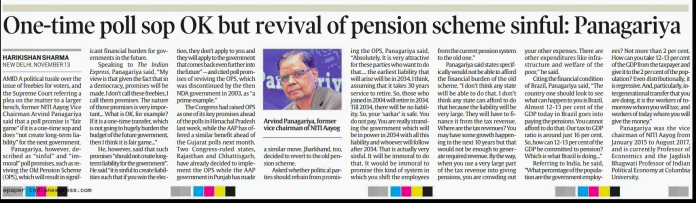

Among prominent economists, besides the RBI, who have condemned the populist election promise is former Niti vice-chairman and professor of economics at Columbia University Arvind Panagariya. In an interview with a prominent national newspaper, he explained that there was no way the governments run by the AAP and INC could fund the old pension scheme.

Panagariya said that the only option left with these state governments was to look at the tax pool, which is people’s money, but there was no money to spare from that revenue collection. “They will have to finance it from the tax revenue. But there are no tax revenues,” he was quoted as saying in the report.

Taking a cue from the professor, even a member of the INC protested. Praveen Chakravarty of the party’s data analytics cell tweeted: “Out of 6.5 crore (65 mn) people in Gujarat, about 3 lakh (300k) are in govt service. The old pension scheme will cost roughly 15% of tax revenues. Why should the top 0.5% of people get 15% of all taxpayers’ money as post-retirement pension?” He added that Panagariya was right.

Chakravarty was perhaps trying to punch a hole in the AAP campaign in Gujarat, but he ended up contradicting his own party, the INC, which is making a similar promise in Himachal Pradesh. This bad economics enjoys the support of Priyanka Gandhi-Vadra too. But embarrassed by this objection from his party colleague, Jairam Ramesh had to intervene, saying that going back to the old pension scheme was not a policy of the central leadership of the INC.

But this did give people ideas that the INC members were not on the same page. To address the awkwardness, Chakravarty tweeted this:

There are other economic affairs commentators who do not endorse going back to the old pension scheme. An article by Gaurav Choudhury in MoneyControl says, “The OPS (old pension scheme) is mainly an unfunded pay-as-you-go system. Pension expenditure alone accounts for 12.4% (average of 2017-18 to 2021-22) of total revenue expenditure of India’s 10 most-indebted states,” citing RBI estimates that show that the pension outgo will continue to be in the range of 0.7-3% of GSDP in these 10 states until 2030-31.

What is the problem with poll-bound states going back to the old system?

There are about 2.5 lakh government employees in Himachal Pradesh, out of whom 1.5 lakh are covered under the new pension scheme. Employees’ associations protested against the new scheme in Shimla, Mandi, Kangra and Solan.

As explained above, the population of people who retire post-2005 will only increase, perpetually adding more burden on the state exchequer.

What makes the AAP promise worse in Gujarat is the fact that it had never formed a government in that state and hence has no idea of its treasury.

The BJP central leadership’s decision to not return to the old scheme is politically negative. After protests by employees in Gujarat, the state government said the new pension would not be applicable to those employees who had joined duty before April 2005 and promised to increase its contribution to the fund to 14% from the 10% of the basic pay plus dearness allowance contributed by the employees in the new pension scheme fund, which had been decided earlier. But it is certainly not returning to the old pension scheme under electoral pressure.

You must log in to post a comment.