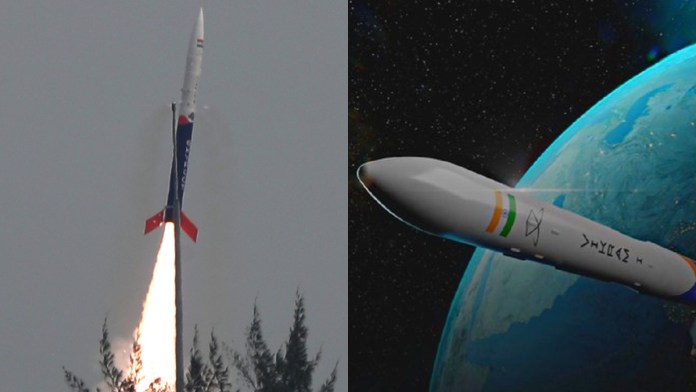

Indian private start-up Skyroot Aerospace has initiated its journey to space, successfully launching its Vikram S rocket in a sub-orbital mission from the sounding rocket complex at Sriharikota spaceport today. The mission marks a new chapter in the country’s space history by making Skyroot the first Indian company to send a privately built rocket to space.

The launch of India’s first private rocket Vikram S, which lifted off from the Indian Space Research Organisation (Isro) launchpad in Andhra Pradesh, is an “important milestone in the journey of India’s private space industry,” Prime Minister Narendra Modi has rightly noted, as he also observed that it was an “accomplishment” of private citizens, two young men “who took full advantage of the landmark space sector reforms of June 2020”.

Who made Vikram S and how?

Pawan Chandana and Bharath Deka founded Skyroot Aerospace in Hyderabad in 2018. It is the first space start-up to sign an agreement for using Isro’s launch and test facilities following the Modi government’s decision to allow private companies in the space sector in 2020.

Skyroot’s private rocket Vikram S, named after the legendary Sarabhai, the father of India’s space programme, reached a peak altitude of 90 km, which is below the internationally recognised 100 km Kamran line that separates the earth from outer space.

The 6 m long rocket that weighed more than 500 kg went for a sub-orbital mission. Vikram S rocket carried three payloads from Space Kidz India, N-Space Tech India and Bazoomq Armenia.

The Vikram S rocket was equipped with four 3D-printed engines and was made of carbon fibre. The vehicle included a single-stage propulsion system powered by solid fuel.

The rocket took off at about 11.30 AM this morning. Vikram S was able to reach an altitude of 89.5 km and a range of 121.2 km before it safely splashed down in the Bay of Bengal. The total flight time of the vehicle was about 300 s.

What’s the objective of this mission besides the entry of the private sector in the Indian space industry?

This mission will help Skyroot Aerospace to approve the technologies that will be used in the next Vikram 1 orbital vehicle which is planned to launch in 2023.

The firm is planning rocket launches that can place satellites in orbits.

From government’s Aryabhatta with Soviet collaboration to privately made Vikram S

Aryabhatta was India’s first satellite, named after the famous Indian astronomer. It was launched on 19 April 1975 from Kapustin Yar, a Soviet rocket launch and development site in Astrakhan Oblast, using a Kosmos 3M launch vehicle. It was built by the Isro and launched by the Soviet Union as a part of the Soviet Interkosmos programme that provided access to space for friendly states.

India has been successfully launching satellites of various types since 1975. Apart from Indian rockets, these satellites have been launched using various vehicles, including American, Russian and European rockets. Isro shoulders the bulk of the responsibility of designing, building, launching and operating these satellites.

India had three continuous successful satellite launches from its first-generation rocket SLV in the 1980s. In the 1990s, the Polar Satellite Launch Vehicle (PSLV) arrived, which allowed India to become self-reliant in launching most of its remote-sensing satellites. However, for heavy geostationary systems, India continued to remain dependent on Europe entirely. The capability to launch geostationary satellites would arrive in the next decade.

In the 2000s, Isro’s workhorse PSLV became the mainstay for successful launches of indigenous satellites from India during the decade. India successfully launched 11 geostationary or geosynchronous satellites during this period, which was equal to the total number of similar launches in the previous two decades put together. India’s first extra-terrestrial mission was successfully executed during this period.

While India had to face failure in launching relatively heavier satellites early on in the 2010s, it did end up launching 27 geosynchronous and geostationary satellites (17 with indigenous, and 10 with European launchers). In that decade, it managed to launch most of its satellites successfully on its own.

This period also saw India enter the exclusive club of nations capable of launching probes to Mars. Isro also improved upon its student/university outreach by launching multiple pico-, nano- and mini-satellites from various Indian universities. This period was marked also by multiple bilateral collaborations with foreign universities and research organizations. The same decade saw the completion of NAVIC, India’s regional navigation system.

In the ongoing decade, Isro aims to conduct 50 launches between 2020 and 2024. Besides increasing the launch frequency to more than 12 a year. A number of extraterrestrial exploration missions including Aditya L1, Chandrayaan 3, Lunar Polar Exploration Mission, Shukrayaan 1 and Mars Orbiter Mission 2 are planned for this decade. A mission to Jupiter after Shukrayaan and a mission to explore the space beyond the solar system have been proposed.

PSLV is expected to undergo its 100th flight mission in the middle of the decade. India’s new low-cost Small Satellite Launch Vehicle made its maiden flight in January 2020 while SCE-200, which is expected to be the powerplant of India’s upcoming heavy and super heavy launch systems, could make the first flight sometime in the middle of the decade. Conducting an orbital human spaceflight before August 2022 is the highest priority for the agency while the long-term goals of the programme include human-occupied space stations and crewed lunar landing.

When did the space domain open to the private sector? How is it faring?

India opened the space sector for private firms in 2020 and allowed them to build rockets and satellites. They have also been allowed to use Isro’s launching facilities.

Isro is assisting private companies to end the space monopoly in the country. The Indian space agency is offering its facilities for testing and launching rockets as well as satellites that are made by private companies.

The Russia-Ukraine war opened up more opportunities for India, with London-based satellite company OneWeb, which is financially backed by Indian mobile telephony and broadband giant Bharti Airtel, turned to India after it was forced to suspend the use of Russian rockets due to sanctions on Moscow. In October, Isro launched 36 satellites for OneWeb on an LVM3 rocket, taking the number of satellites it has in space to 462.

OneWeb plans to send a total of 648 satellites into space. With Russia ruled out because of the US-led Nato countries’ sanctions on it, India is stepping up to launch the rest as well.

Size of Indian space exploration market

India’s funding for space research is just a fraction of the American or Chinese expenditure but is also quite economical when compared to the competition. It claims only around 2% of the global space market share, but experts expect the ongoing reforms can help boost the sector further.

Isro has gradually built the reputation of a cost-effective and reliable partner, launching its own research-oriented space missions and also partnering with more than 30 countries to help launch nearly 400 of their satellites.

Government estimates show the Indian space industry was worth around $ 7 billion in 2019 but has the potential of growing to $ 50 billion by 2024.

“India deserves to have a bigger share of the global space economy. We should be looking at at least 8-10%” says businessman Pawan Goenka, who heads INSPACe, India’s space regulator and promoter that coordinates between private space firms and Isro.

How are the financials of the company that made Vikram S?

While Singaporean wealth fund GIC backs the company, the Hyderabad-based firm is eyeing to cut development costs by up to 90% to launch small satellites. Skyroot hopes to achieve cost savings through rocket architecture that can be assembled in less than 72 h using composite materials.

The launch of the Vikram S rocket has marked the entry of private players in India’s space sector.

Are there competitors of Skyroot in the private segment of the space market?

Ten other private firms have either launched or are close to launching their products. Pixxel, another start-up, is working on a product that will help provide images that can help in mining and disaster management.

Bengaluru-based start-up Digantara is mapping space debris for the world. Other companies such as Dhruva, Agnikul and Bellatrix are trying to make their mark.

Thriving space start-ups have given more opportunities to young Indians to work in the country instead of going abroad to achieve their dreams. “It has now become more accessible for aerospace engineers to have more scope in India,” says Himani Varshney, 25, an engineer who works at Skyroot.

The Indian National Space Promotion and Authorization Center (IN-SPACe) has more than 30 applications from entities wanting a nod for launch segment activities.

Within months of forming its directorates and beginning operations, IN-SPACe has nearly 300 entities registered expressing their interest in carrying out business or other activities in the Space sector.

Out of these, 89 are startups, 94 are classified as industry and 30 as MSMEs. There are also applications from academia, NGOs and others.

“We have already cleared four proposals in the last six months, including the launch of Skyroot, which is scheduled to launch on 18 November. But this is only the beginning. Among the many applications we have, there are those seeking promotions where we will help them get mentors, expert consultancy and more,” Vinod Kumar, director, directorate of promotions, IN-SPACe, said. Including the 30-plus applications seeking IN-SPACe’s nod for launch vehicle-related activities, there are a total of 158 applications the agency is vetting on a case-by-case basis. Most of them (141) are proposals seeking authorisation.

PK Jain, director-project management and authorisation, IN-SPACe, says the applications for launch segment activities are those related to the development and testing of launch vehicles or associated systems and subsystems.

Of the 158 applications, most are for satellite projects (70), while there are 17 seeking approval for applications and eight for ground segment-related activities. Comparatively, in August 2020, IN-SPACe had 97 applications seeking its permission to carry out Space activities, including 21 for launch vehicles and 54 for satellites.

Proposals that are in an advanced stage of consideration by IN-SPACe include those from Agnikul Cosmos, Bellatrix Aerospace, Astrome Technologies, Tathya, Manastu Space, Dhruva Space, Scanpoint Geomatics Ltd (SGL), Pixxel India, OneWeb India Communications, Hughes Communications, MTAR Aerospace, Ananth Technologies, LBS Institute of Technology for Women and ITCA, Bengaluru - 75 Student Satellite project.

Of these, Agnikul, which already has some clearances, is targeting a year-end launch of its sub-orbital launch vehicle, while Bellatrix has already expanded with new facilities, Dhruva Space and Pixxel will launch their payloads on November 26 onboard a PSLV.

The other companies are making progress with technology demonstration and in-house testing of systems.

What are the challenges for private players in the Indian space market?

Private companies in India cannot expect to make profits overnight, as it is a long-term business beginning with the phase when a rocket launch is planned to the phase of designing the rocket and then a satellite and finally launching it. It’s not over yet. The space entrepreneur must then find a market and only then think of returns. In such a scenario, only such businessmen will venture into the market who see the money coming in.

This is not an easy sector. It calls for a lot of hard work for several years before private players in India can find it vibrant.

You must log in to post a comment.